Diesel Controversy: “Retrofitting and exchange campaigns for passenger cars alone are hardly enough to meet the limits in cities.”

Jülich expertise

Jülich, 27 September 2018 – In view of the impending driving bans, various solutions for diesel passenger cars are currently under discussion. Retrofitting and exchange programmes are intended to help reduce nitrogen oxide pollution in city centres in order to comply with EU limit values. Atmospheric researcher Dr. Franz Rohrer from Forschungszentrum Jülich doubts that these measures alone will be sufficient to comply with the limit values in large German city centres. For over 20 years, he and his colleagues have been researching how emissions from transport affect air quality. Diesel cars in the cities are only a small part of the problem, however.

How effective are the measures that are currently being pursued?

Franz Rohrer: The EU has set a limit of 40 micrograms of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) per cubic metre for the annual average at a monitoring station. This value can hardly be influenced to the desired extent by retrofitting and exchanging diesel cars. Specifically, I expect that these solutions will not be sufficient for all cities with an annual average of 50 micrograms of NO2 and more. This is partly due to the fact that the diesel cars in question are not the main cause of nitrogen oxides in German city centres. Diesel cars are responsible for only about 33 per cent of nitrogen oxide traffic emissions. Around 50 per cent of nitrogen oxides from traffic, however, come from vans, lorries and buses.

Where do these values come from?

F.R.: We published the above figures in the Faraday Discussions trade journal as part of an extensive analysis of emissions from transport. The publication was peer-reviewed by independent scientists. The values refer to 2015. I assume that there is no great difference to this today, because the framework conditions have changed very little since then.

How do you explain the high values for vans, buses and lorries?

F.R.: Today, practically all large commercial vehicles are equipped with an SCR catalytic converter that removes the nitrogen oxides from the exhaust gas with the aid of uric acid. But there’s a catch in this technology. Today’s SCR catalytic converters only start functioning at a temperature of about 170 degrees Celsius. What is more, they only work efficiently from 250 degrees Celsius in the catalytic converter housing. In the stop-and-go of an inner city, this temperature is usually not reached. As a result, vehicles in urban traffic emit much more nitrogen oxides than officially stated.

What else should one keep in mind?

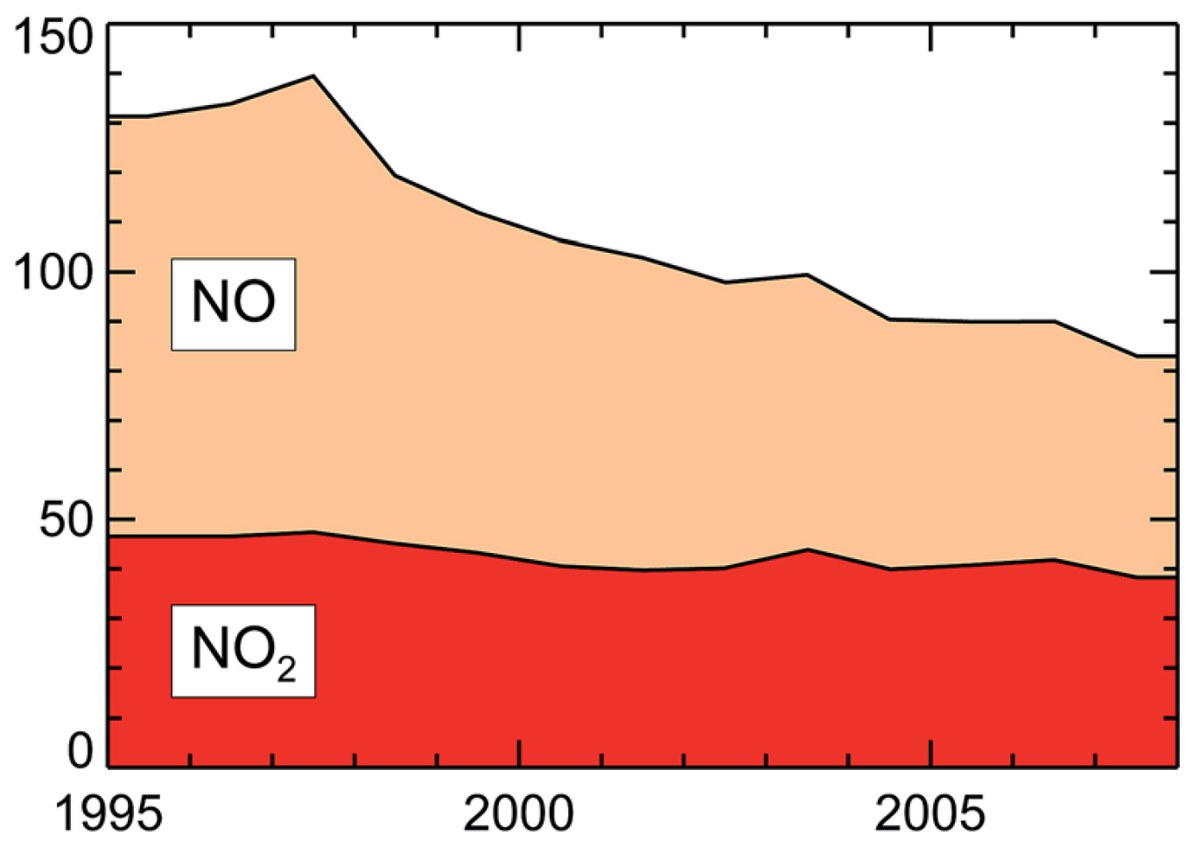

F.R.: The German Environment Agency has been measuring the nitrogen oxides NO and NO2 at traffic junctions in German city centres for decades. These measurements show that the nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentration to which the EU limit value refers has not decreased to the same extent as have nitrogen monoxide (NO) concentrations. The measurements substantiate that there is a strongly non-linear relationship between NO2 concentrations and NOx concentrations (= NO + NO2), which are a measure of traffic emissions.

How does this difference come about?

F.R.: In the exhaust gas of a vehicle, one finds practically only nitrogen monoxide (NO) and only a little nitrogen dioxide (NO2) (approximately about 15 per cent). Only later, in a reaction with ozone in the ambient air, is the NO emitted by the vehicle converted into nitrogen dioxide (NO2). How much nitrogen dioxide is produced therefore also depends on the ozone in the ambient air, which is transported to the cities by wind. This so-called background concentration of ozone has been very constant in Germany in recent years and shows practically no regional differences.

Only part of the nitrogen monoxide emitted by vehicles is actually converted into nitrogen dioxide. In essence, this means that if the ozone present has already been completely converted into NO2 by NO, NO2 cannot continue to rise even if the NO values continue to rise. Putting it the other way around, this means that if nitrogen dioxide is to be reduced at traffic junctions, the nitrogen monoxide emitted must be reduced to a much greater extent than nitrogen dioxide values measured make it appear.

For a city like Cologne, where the annual average NO2 concentration at the Clevischer Ring monitoring station is currently over 60 µg/m³ (micrograms per cubic meter), our investigations show that it is not sufficient to reduce the total nitrogen oxide traffic emissions by one third in order to lower the limit value to 40 µg/m³. This would primarily reduce the concentration of NOx (= NO + NO2) by about one third. The nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentration, to which the EU limit value refers, would decrease by only 15 per cent to 52 µg/m³. If we want to get below 40 µg/m³ in this case, we would have to reduce traffic emissions by a factor of 2.6 - that is, by almost two thirds.

What does that mean in concrete terms?

F.R.: Considering that all diesel cars together cause just one third of nitrogen oxide traffic emissions in German cities, one can imagine how small the effect of retrofitting and exchange campaigns for diesel cars will be. My example shows: even if all diesel cars in Cologne were taken off the road, the NO2 value at Clevischer Ring could probably be reduced by no more than 15 per cent. That would be far too little to comply with the EU threshold there.

What other measures would there be to comply with the EU directives?

F.R.: Another or an additional possibility would be to upgrade lorries and buses so that their SCR catalytic converters will also be active in driving situations where the catalytic converters’ temperatures are currently still too low to remove the nitrogen oxides. For example, this could be achieved with the aid of a heating coil that winds around the catalytic converter and maintains the temperature there at a minimum of 250 degrees Celsius in all driving situations. It probably would be much less complex and cheaper to put this into practice than the solutions that are currently discussed for diesel cars. At the same time, far more would be achieved with this than with only retrofitting or with driving bans for diesel cars.

Sources:

Christian Ehlers, Dieter Klemp, Franz Rohrer, Djuro Mihelcic, Robert Wegener, Astrid Kiendler-Scharr, Andreas Wahner

"Twenty years of ambient observations of nitrogen oxides and specified hydrocarbons in air masses dominated by traffic emissions in Germany"

Faraday Discuss., 2016, 189, 407, DOI: 10.1039/c5fd00180c

Contact:

Dr. Franz Rohrer, Dr. Dieter Klemp, Dr. Robert Wegener

Institute of Energy and Climate Research, Troposphere (IEK-8)

Tel.: +49 2461 61-6511

E-Mail: f.rohrer@fz-juelich.de

Press contact:

Tobias Schlößer

Unternehmenskommunikation

Tel.: +49 2461 61-4771

E-Mail: t.schloesser@fz-juelich.de