Membranen

Wrapping of Nanoparticles by Lipid-Bilayer Membranes

Membrane budding and particle uptake is important for the communication of cells with their environment, e.g. for endocytosis, phagocytosis, and parasite or virus entry. Also, various potential applications of nanoparticles in complex materials require a better understanding of their cellular toxicity. Furthermore, nanoparticles can be used for targeted drug delivery, for cancer therapy, and as membrane-makers for biomedical studies.

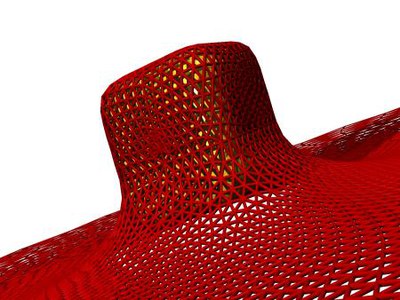

We study the passive endocytosis of nanoparticles between ten and a few hundred nanometers in size that are wrapped in lipid bilayer membranes. Upon wrapping, the membrane deformation energy increases while the adhesion energy due to the attractive interaction between particle and membrane decreases. Numerical calculations with triangulated surfaces allow the calculation of deformation energies for various particle shapes.

We characterise nanoparticle wrapping analogously to thermodynamic phase transitions. While partially-wrapped states are found only in membranes with tension in the case of spherical nanoparticles, cube-like, rod-like, and ellipsoidal nanoparticles show shallow and deep partially-wrapped states also without tension. Here, shape matters! Not only the aspect ratio, but also the local curvature distribution on the nanoparticle surface controls binding and wrapping. This is the first crucial step for the interaction of nanoparticles with biological cells.

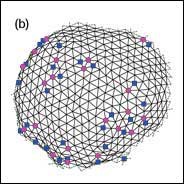

Fluctuating shells under pressure

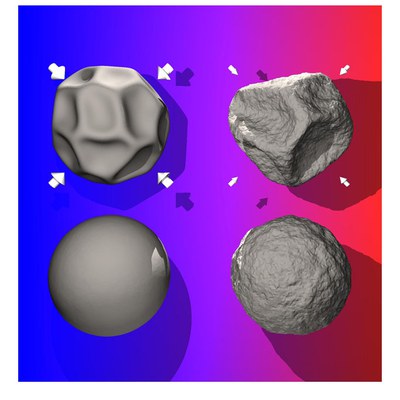

A thin spherical shell can be considered as an elastic membrane with shear modulus, bending rigidity and a non-zero curvature. On a micrometer and submicrometer scale, examples of these shells range from synthetic hollow polyelectrolyte capsules with important technological applications, through to biologically relevant systems such as red blood cells and spherical virus capsids. In the absence of thermal fluctuations, the stability of elastic shells against external forces such as a uniform pressure field or a point-like indentation depends on the ratio between the size of the shell and the thickness of the wall. As in flat membranes, thermal fluctuations are expected to influence the mechanical response of a deformed shell by the renormalization of elastic constants.

However, the fluctuations of thin shells are qualitatively different from those in flat elastic membranes due to the coupling of in-plane stretching modes and bending modes by the curvature.We study the deformations of these shells using Monte Carlo computer simulations and perturbation theory, including the effects of curvature and external pressure. We show that thermal fluctuations reduce the critical buckling pressure and soften the mechanical response on point-like indentations.

Budding Induced by Conical Inclusions

Budding and vesiculation of lipid bilayers is the first step for material transport in biological cells. Bud formation can be induced by curved inclusions, such as asymmetric proteins or viruses that are partially adhered to the bilayer.

Whereas curved inclusions in a planar membrane experience a repulsive membrane-mediated interaction, we find an effective attraction for inclusions on a bud. This attraction is caused by the screened repulsion of inclusions on a curved membrane. Using a model that contains bending energy only, we find an optimal bud radius and therefore a spontaneous curvature c0 for a given density of inclusions, corresponding to catenoid-like membrane-deformation patches around the inclusions. For budding from a mother vesicle, bending energy alone generates a line of degenerated ground states for the bud radius as a function of number of inclusions per bud. Translational entropy of the inclusions lifts that degeneracy and free-energy minimization then allows a unique prediction of bud radii.

Crumpling of thin elastic sheets

The deformation of thin elastic sheets is a fundamental problem with many practical applications to different physical and biological systems. Among these systems are macroscopic materials extending from thin steel plates via thin rubber films to paper sheets, mesoscopic materials like clay platelets, the membrane of biological cells and giant vesicles, but also microscopic materials like virus particles and carbon nano-tubes.

Using computer simulations we investigated the effect of self-avoidance on the shapes, mechanical properties and fold length distributions of crumpled elastic sheets.

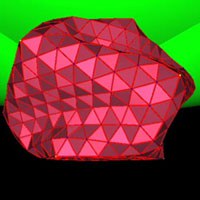

Buckling of virus capsids

The genome of a virus is contained in a protective cage known as the viral capsid. A viral capsid has a remarkably regular structure and is built up from a fixed number of copies of a single or a few kinds of capsid protein. Its geometry is that of an icosahedron or a helical cylinder, but more complex structures also exist. We investigate the mechanical properties of icosahedral virus shells by computer simulations. We predict the elastic response for small deformations, and the buckling transitions at large deformations which depend both strongly on the number of elementary building blocks, the shear and bending elasticity of the shell and the confining geometry.

Polymer-decorated membranes

Polymer-membrane interactions are relevant in many complex systems, ranging from membranes of biological cells to microemulsions. For example, polymer boosting in ternary microemulsions enhances the oil-water mixing efficiency of the surfactant. Polymers anchored to membranes suppress fluctuations of the membrane conformation, i. e. polymer addition effectively stiffens the membrane. Using Monte-Carlo simulations, we determine effective curvature-elastic constants for polymer-decorated membranes. In particular, we investigate the effect of self-avoidance within a single polymer chain. This has been extended to investigate other polymer architectures like star polymers. With increasing arm number of anchored stars, the bending rigidity is found to increase strongly, while the saddle-splay modulus remains constant.

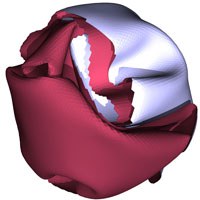

Abschnüren kristalliner Bereiche in Flüssigmembranen

In einer biologischen Zelle wird die Bildung kleiner Vesikel an der Plasmamembran - ein Prozess namens Endozytose - von der Adsorption von Clathrin-Proteinen gesteuert. Diese Moleküle bilden auf der Membranoberfläche lokal ein regelmäßiges, sechseckiges Netzwerk aus. Somit entspricht die Bildung von Vesikeln aus einem solchen Bereich physikalisch dem Ausschnüren von kristallinen Bereichen, die in Flüssigmembranen eingebettet sind. Hier wird die Ausschnürung von der Linienspannung der Bereichsgrenze und von der spontanen Krümmung c0 getrieben. Wir benutzen Monte-Carlo-Simulationen an dynamisch-triangulierten Oberflächen und Skalierungsparameter, um diesen Prozess zu untersuchen. In kristallinen Phasen entstehen bei der Bildung von Kugelschalen Gitterfehler. In einem aus Dreiecken aufgebauten hexagonalen Gitter, das in der ebenen Phase nur sechsfach koordinierte Dreieckspitzen enthält, sind dies fünf- und siebenfach koordinierte "Disklinationen" (siehe Abbildung). Wir stellen fest, dass die Defekte an der Grenze entstehen und dann ins Innere diffundieren. Darüber hinaus ergeben unsere Simulationen: Je größer der kristalline Bereich ist, desto kleiner kann die spontane Krümmung c0 sein, damit es zu einer Ausschnürung kommt. Dieses widerspricht bisherigen Voraussagen.

Fortgeschrittene Flickerspektroskopie an flüssigen Vesikeln

Die Formen und Fluktuationen von Flüssigmembranen werden von ihrer Krümmungselastizität gesteuert, die durch zwei elastische Konstanten, die Biegesteifigkeit und die spontane Krümmung, gekennzeichnet ist. Das Spektrum der Membranfluktuationen liefert Informationen über die Werte der elastischen Konstanten. Die Analyse von Membranfluktuationen - Flickerspektroskopie genannt - hat sich bisher auf quasikugelförmige Vesikel beschränkt. So kann zwar die Biegesteifigkeit, nicht aber die spontane Krümmung bestimmt werden. Wir haben eine neue Methode entwickelt - die fortgeschrittene Flickerspektroskopie riesiger, nicht-kugelförmiger Vesikel, die es ermöglicht, beide Parameter gleichzeitig zu messen. Unsere Analyse basiert auf einer großen Menge Referenzdaten willkürlich triangulierter Oberflächen, die aus Monte-Carlo-Simulationen gewonnen wurden. Die Methode wurde auf die thermischen Trajektorien von Vesikelformen und auf die elastische Response von zwitterionischen Membranen auf transmembrane pH-Gradienten angewendet. Die neue Technik ermöglicht es, die Membrankrümmung als Funktion von Umgebungsbedingungen mühelos zu charakterisieren.

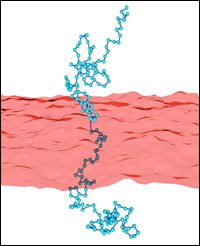

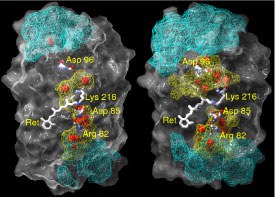

Wassermoleküle und Wasserstoffbrücken-Netzwerke in Bacteriorhodopsin - Molekulardynamik-Simulation vervollständigt Kristallstruktur

In die Struktur von Bacteriorhodpsin (bR) sind Wassermoleküle eingebaut. Die räumliche Verteilung der Wassermoleküle und das zugehörige Netzwerk aus Wasserstoffbrücken-Bindungen wurden mit Hilfe von Molekular-dynamiksimulationen in der Grundzustands-Konformation untersucht. Bei dieser Untersuchung wurde der Grundzustand gewählt, um nachzuweisen, dass sogar die Struktur mit der niedrigsten Menge an Wassermolekülen ein dichtes und stark fluktuierendes Wasserstoffbrücken-Netzwerk im fast hydrophoben Teil von Bacteriorhodopsin enthält. Das Protein wurde dazu in eine vollständig hydratisierte Lipid-Bilayer-Membran eingebettet. .

Im Vergleich zu Kristallstrukturdaten wurde in unserer Simulation eine viel höhere durchschnittliche Anzahl interner Wassermoleküle gefunden (44 statt 18). Diese Diskrepanz geht auf die hohe Beweglichkeit des H2O zwischen verschiedenen Positionen zurück. Im Durchschnitt finden wir 20 eingeschlossene und 24 diffusive Wassermoleküle im bR. Die Zeit für den Austausch aller diffusiver Wassermoleküle beträgt etwa 200 ps. Die durchschnittliche Verweilzeit eines diffusiven Wassermoleküls im Inneren von bR ist ungefähr 52 ps.

Zur Beschreibung der Wasserstoffbrücken-Netzwerke im Protein benutzen wir ein geometrisches Konstrukt, das auf dem Grotthuss-Modell beruht. So bilden sich zwischen der zytoplasmatischen Oberfläche und dem geladenen Asp96-Rest Ketten aus Wasserstoffbrücken aus. Es zeigt sich, dass die Länge einer Kette durchschnittlich aus 5 Bindungen besteht. Die durchschnittliche Lebensdauer einer ununterbrochenen Kette liegt in der Größenordnung von 0,045 ps. Die durchschnittliche Raumverteilung der Wasserstoffbrückenbindungen zwischen der zytoplasmatischen Oberfläche und Asp96 weist auf eine Art Trichter hin, der auf Asp96 gerichtet ist. Diese Untersuchung schafft eine neue Grundlage für den Protonen-Transfer über stark fluktuierende Wasserstoffbrücken-Netzwerke, um den Mechanismus des Protonenpumpens zu klären (2004).